Managing and running an independent, high producing group or team is easier said than done. It’s a multi-faceted task that requires, among other things, empathy, emotional intelligence, and strategic thinking. It’s a job that places you, the manager, in different roles, going from coach and mentor in one instance to disciplinarian in the next.

Management and leadership are not subjects that have been lacking in observation and exploration. There are hundreds of competing theories on what makes a good manager, some of them produce results and others don’t.

Luckily, Harvard Business Review packaged the 10 best articles published in their magazine into an easy-to-read book that offers incredible and deep insight on what management styles work in which situations and how to build a better environment to meet your objectives.

I’d like to share eight quotes, one from each article, that I found especially powerful.

Coercion Does Not Lead to Success

“[T]he coercive style is the least effective in most situations. Consider what the style does to an organization’s climate. Flexibility is the hardest hit. The leader’s extreme top-down decision making kills new ideas on the vine. People feel so disrespected that they think, “I won’t even bring my ideas up—they’ll only be shot down.” Likewise, people’s sense of responsibility evaporates: unable to act on their own initiative, they lose their sense of ownership and feel little accountability for their performance.”

— p. 6 (Leadership That Gets Results); bolding mine.

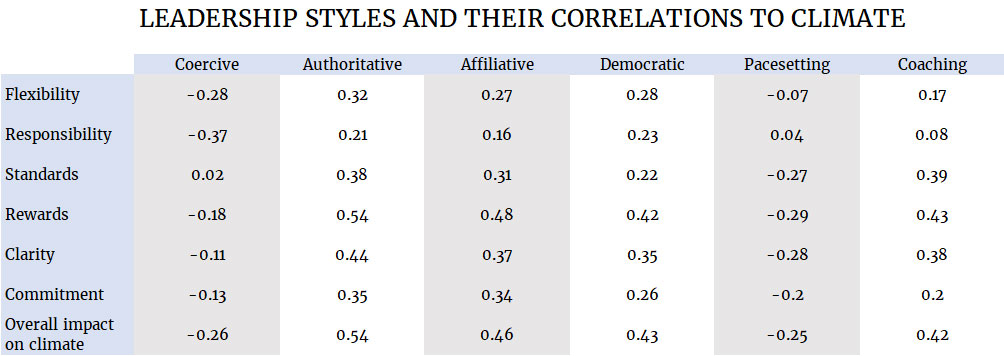

What other styles are there and how do they impact performance? The article goes into further detail, but this table will give you a bird eyes’ view:

An Employee Who’s Not Dissatisfied is not Necessarily Satisfied

“The findings of these studies, along with corroboration from many other investigations using different procedures, suggest that the factors involved in producing job satisfaction (and motivation) are separate and distinct from the factors that lead to job dissatisfaction. Since separate factors need to be considered, depending on whether job satisfaction or job dissatisfaction is being examined, it follows that these two feelings are not opposites of each other. The opposite of job satisfaction is not job dissatisfaction but, rather, no job satisfaction; and similarly, the opposite of job dissatisfaction is not job satisfaction, but no job dissatisfaction.”

— p. 37 (One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?); bolding mine.

The implication is that the answers to ‘what makes my employees unhappy’ and ‘what makes my employees happy’ are separate and distinct, and by focusing on solving the issues that make them unhappy you won’t necessarily be creating an environment that makes them happy.

Protecting Employees From Failure is a Surefire Way of Demotivating Them

“The [set-up-to-fail] syndrome usually begins surreptitiously. The initial impetus can be performance related, such as when an employee loses a client, undershoots a target, or misses a deadline…[T]he syndrome is set in motion when the boss begins to worry that the employee’s performance is not up to par.

The boss then takes what seems like the obvious action in light of the subordinate’s perceived shortcomings: he increases the time and attention he focuses on the employee. He requires the employee to get approval before making decisions, asks to see more paperwork documenting those decisions, or watches the employee at meetings more closely and critiques his comments more intensely.

These actions are intended to boost performance and prevent the subordinate from making errors. Unfortunately, however, subordinates often interpret the heightened supervision as a lack of trust and confidence. In time, because of low expectations, they come to doubt their own thinking and ability, and they lose the motivation to make autonomous decisions or to take any action at all. The boss, they figure, will just question everything they do—or do it himself anyway.

Ironically, the boss sees the subordinate’s withdrawal as proof that the subordinate is indeed a poor performer…So what does the boss do? He increases his pressure and supervision…Eventually, the subordinate gives up on his dreams of making a meaningful contribution.”

— p. 52 (“The Set-Up-to-Fail Syndrome“) ; bolding mine.

How do you get out of the vicious cycle?

The authors, Jean-François Manzoni and Jean-Louis Barsoux, recommend that the supervisor and the employee have a discussion in a neutral location to go over expectations and objectives. And if the supervisor wants to increase direct supervision, this should be communicated with clarity, explained, and the increase should be temporary.

Rookie Managers Need Training Too

“Most organizations promote employees into managerial positions based on their technical competence. Very often, however, those people fail to grasp how their roles have changed—that their jobs are no longer about personal achievement but instead about enabling others to achieve, that sometimes driving the bus means taking a backseat, and that building a team is often more important than cutting a deal. Even the best employees can have trouble adjusting to these new realities. That trouble may be exacerbated by normal insecurities that make rookie managers hesitant to ask for help, even when they find themselves in thoroughly unfamiliar territory. As these new managers internalize their stress, their focus becomes internal as well. They become insecure and self-focused and cannot properly support their teams. Inevitably, trust breaks down, staff members are alienated, and productivity suffers.”

— p. 78 (“Saving Your Rookie Managers From Themselves“); bolding mine.

The article also mentions that many higher level managers often let rookie managers learn the job on their own, which fails more often than it succeeds. Like all employees, freshman managers need training, direction, and feedback.

Great Managers Know the Pieces on the Chess Board Differ From Each Other

“[A]t the very heart of their success lies an appreciation for individuality. This is not to say that managers don’t need other skills. They need to be able to hire well, to set expectations, and to interact productively with their own bosses, just to name a few. But what they do—instinctively—is play chess. Mediocre managers assume (or hope) that their employees will all be motivated by the same things and driven by the same goals, that they will desire the same kinds of relationships and learn in roughly the same way.”

— p. 109 (“What Great Managers Do“); bolding mine.

Marcus Buckingham, the author, goes on to explain by example how great managers are able to flexibly mold the positions in the company around the strengths of the employees, which gets more out of the team at a lesser cost. First, you maximize each individual’s strength by giving them a scope that fits those strengths. Second, you save on firing, hiring, and re-training.

No Matter the Decision, it’s More Likely to be Widely Accepted if the Process by Which it’s Made is Deemed Fair

“[John W. Thibaut’s and Laurens Walker’s] research established that people care as much about fairness of the process through which an outcome is produced as they do about the outcome itself. Subsequent researchers such as Tom R. Tyler and E. Allen Lind demonstrated the power of fair process across diverse cultures and social settings.

We discovered the managerial relevance of fair process more than a decade ago, during a study of strategic decision making in multinational corporations. Many top executives in those corporations were frustrated—and baffled—by the way the senior managers of their local subsidiaries behaved. Why did those managers so often fail to share information and ideas with the executives? Why did they sabotage the execution of plans they had agreed to carry out? In the 19 companies we studied, we found a direct link between processes, attitudes, and behavior. Managers who believed the company’s processes were fair displayed a high level of trust and commitment, which, in turn, engendered active cooperation. Conversely, when managers felt fair process was absent, they hoarded ideas and dragged their feet.”

— pp. 117 & 120 (“Fair Process: Managing in the Knowledge Economy“); bolding mine.

Mentioned towards the end of the article is that a fair process shouldn’t be conflated with a democratic process. You can have an authoritarian style of leadership and still employ a fair process. By fair process, what the article is referring to are rules-of-the-game that are clear, understood, and based on merit.

Institutionalize Failure and How to Learn From It

“Put simply, because many professionals are almost always successful at what they do, they rarely experience failure. And because they have rarely failed, they have never learned how to learn from failure. So whenever their single-loop learning strategies go wrong, they become defensive, screen out criticism, and put the ‘blame’ on anyone and everyone but themselves. In short, their ability to learn shuts down precisely at the moment they need it the most.”

— p. 134 (“Teaching Smart People How to Learn“); bolding mine.

Chris Argyris goes on to mention that changing learning culture in a company needs to start at the top. Reports need to see that their supervisors are living and breathing a different sort of learning, so that they too can feel comfortable with the vulnerability of being wrong.

I would add that, apart from higher level management living the learning philosophy they want to inculcate, these managers also must be aware of how they are responding to failure. They need to prove that the employee has no reason to get defensive, because a mistake on its own is not a failure. Mistakes are only failures if you’re not learning from them.

We Are All Biased, Even When We Think We Aren’t

“Imagine that you are making a decision in a meeting about an important company policy that will benefit some group of employees more than others. A policy might, for example, provide extra vacation time for all employees but eliminate the flex time that has allowed many new parents to balance work with their family responsibilities. Another policy might lower the mandatory retirement age, eliminating some older workers but creating advancement opportunities for young ones. Now pretend that, as you make your decisions, you don’t know which group you belong to. That is, you don’t whether you are a senior or junior, married or single, gay or straight, a parent or childless, male or female, healthy or unhealthy. You will eventually find out, but not until after the decision has been made. In this hypotehtical scenario, what decision would you make?…

…This thought experiment is a version of John Rawls’s concept of the ‘veil of ignorance,’ which posits that only a person ignorant of his own identity is capable of a truly ethical decision.“

— pp. 171–172 (“How [Un]Ethical Are You?“); bolding mine.

Most of us aren’t consciously biased. The article assumes as much.

It’s not arguing that we are purposefully discriminatory.

Rather, it’s arguing that it’s impossible to be subconsciously unbiased because we all have our own backgrounds and experiences that dictate how we associate different things and events. These associations, or patterns, can be wrong sometimes.

Someone who seeks to be more aware of these subconscious biases can start to question their assumptions and collect data that allows them to put their beliefs to the test. For example, you can audit your hiring processes and see if there are any patterns which suggest the presence of an unconscious bias. For example, a company that doesn’t consciously discriminate by age may still be hiring candidates predominately from a specific age group. By comparing the data to your assumptions, we become cognizant of these latent biases and can correct them.

A Treasure Trove of Leadership and Management Lessons

HBR’s compendium on how to manage people is an excellent resource for managers and future managers at all levels. It’s a quick read and deeply insightful.

If you like this topic, you may also enjoy “Eating Soup With a Knife: Lessons in Management,” which discusses how teams of specialists can be better coordinated with the bigger picture through the use of smart metrics that hold individuals accountable and in tune with higher level objectives.