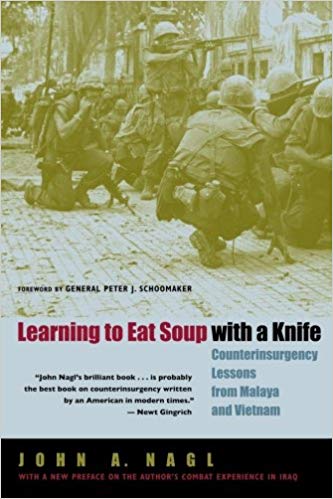

In Malaysia, the British faced a similar situation to the American experience in Vietnam. Yet, whereas the Americans failed to defeat the Vietnamese guerrillas, the British succeeded in building a stable democracy. Why did the two powers see different results? Lt. Col. John Nagl answers this question in Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife, first published in 2005.

This book was a must-read in the U.S. Army during and after the surge in Iraq, and has influenced military organization and tactics.

For us civilians, the book also offers an important lesson in management.

Business Growth, Decision-Making, and Knowledge Problems

When a team is small, it’s easy for central leadership to impart its vision and enforce it by guiding the actions and decisions of each team member. As a company grows, and the responsibilities of each team member grow with it, it becomes more and more difficult to control individual decisions.

Growing companies and growing teams imply expanding divisions of labor. There’s more specific work to do and you hire specific people to fit specific roles. Specific work is specialized work, with its own learning curve, its own terrain, and its own challenges.

Growing companies and growing teams imply expanding divisions of labor. There’s more specific work to do and you hire specific people to fit specific roles. Specific work is specialized work, with its own learning curve, its own terrain, and its own challenges.

When obstacles become more specific, it’s ideal for the specialist to overcome them because they are in the best position to know their field.

This evolution is easier to write about than it is to actually develop in practice.

Oftentimes, this process of growth and the necessary decentralization that comes with it finds trust an obstacle. Newer companies, or businesses that don’t have specific procedures institutionalized for certain roles, find it especially hard to trust people to produce the expected results.

Most SEO teams, for example, have very specialized roles that are filled by experts, even if these experts are organized under the leadership of a single manager. If there’s a change to the algorithm that requires a specialist to figure out how this change affects their work, but there’s no trust between the manager and the specialist, it may be the manager who attempts to direct the specialist’s work. But it’s the specialist who has specialist knowledge, and by taking control the manager is losing the benefit of the specialist’s understanding of her own domain.

Likewise, in a dental office, the dentist may hire an office administrator whose a specialist in training front desk staff, organizing expenses and billing, and other tasks that are unique to the practice and how it does things. As this person digs deeper and deeper into their role, their understanding of the terrain starts to exceed that of anybody else. If they aren’t allowed to use that knowledge because they aren’t trusted to make decisions on their own, that represents a waste and a limit on the practice’s growth.

And it’s not just about losing the advantage of the specialist’s knowledge when dictating decisions in their domain to them. The problem is suffered by the leader as well, who now has to spend time making decisions out of her direct wheelhouse to instead [micro]manage other team members.

Another common obstacle suffered by growing businesses, and one that can act as a limit to that growth, is the issue of diverging visions and values.

My own goals and objectives as marketing director are sometimes different from those of my team members. I had a pay per click specialist who really wanted to learn a set of analytical tools. These tools were redundant for us and it was a waste of time for the company, yet this person decided to move forward with setting all these tools up for all of our clients. We haven’t used the tools since and it took time away from this person learning what I deemed to be much more valuable information, the ins-and-outs of our clients’ businesses, products, and customers.

[optin-monster-shortcode id=”wbw80mm0fxs0v0dhpgku”]I found myself centralizing decision-making at the expense of giving the benefit of the doubt to the specialist’s knowledge because I wasn’t guaranteed that the specialist would use that knowledge in the most mutually beneficial way.

Other companies and teams suffer from very similar issues. It’s not always easy to get employees to do what is most productive for the company, versus most productive for their careers or for whatever interests they may have. Sometimes the goals are so misaligned that the employee hardly does work at all. It reminds me of clients who suffer problems training good front desk staff that can close a difficult lead.

My father was a school teacher and I learned from his experience that people only learn from you if they are interested in doing so. If goals, values, and visions are not aligned, this can create tensions that restrain the decentralization and growth process in a business.

These very real issues are important because decentralization allows the company to get better and better at what it does. By giving specialists decision-making power, and by deferring to their knowledge, you give your team the freedom to grow the business for you and much more effectively than you could on your own. One person can only know so much and focus on so many things, but the more decentralized a team the more each member can specialize and the more things that team can do.

Decision-Making and Knowledge Problems in Malaysia and Vietnam

The wars in Vietnam and Malaysia were very different from wars like World War II. There was no enemy army arrayed in conventional formations along an objective front. Rather, these were predominately guerilla wars — even conventional Vietnamese units oftentimes fought using guerrilla tactics and in support of the insurgent Viet Minh.

In guerrilla warfare, there is no front, there is no enemy looking to wage a determining battle. Instead, the enemy is spread out, hard to find, and focused more on undermining your authority. In Vietnam, the North Vietnamese and Viet Minh started 80 percent of all engagements during the war, a testament to how difficult it was for the Americans to find, engage, and destroy the enemy, something which was standard during World War II and even during the Korean War.

In fact, guerrilla wars are less about war and more about politics. Guerrilla forces tend to replace occupying forces’ attempts to arbitrate disputes and dispense justice. They thrive in countries with poor governance and failing institutions.

American NCOs and junior officers tried to communicate these differences to their commanders, and innovation at the junior officer level to deal with the inadequacies of the obsolete overall strategy were never supported, institutionalized, or prolonged. Rather, American commanders continued to stress ineffectual strategies and tactics, like encirclements that the enemy simply escaped from because they knew the terrain better, were equipped with lighter loads (and therefore faster), and had the support of the local population.

Even supposed large-scale experiments to implement new tactics around a strategy of separating the civilian population from the Viet Minh, and providing this population with the security and governance it needed, were not committed to or hamstrung by the use of these forces for more conventional — less effective — tactics (see Kevin Boylan’s Losing Binh Dinh for a spectacular case study looking at the failed pacification program in the province of Binh Dinh).

The British went about things the opposite way in Malaysia. It must be noted that the British had more experience in this type of conflict given that as an empire the main function of its army was to keep control of the colonies. It had decades to learn how to provide security to a local population and slowly marginalize the insurgents, without marginalizing the civilians that often support them.

To do this, the British put a heavy emphasis on developing doctrine around the reality in the field. This meant listening to NCOs and junior officers on what tactics work and don’t work.

Just as importantly, the British chose the right metrics by which to gauge the effectiveness of their strategy. By using the right metrics, they were able to adjust the plan when necessary and in a way that made the soldiers on the ground more effective at reaching the ultimate goal.

Furthermore, the British listened to the specialists they had, implementing the advice of people they knew understood the specifics of their particular section of the conflict. Unsurprisingly, the British were successful in Malaysia, just as they were in Kenya and Singapore.

This success had nothing to do with the quality of the personnel. It had everything to do with how those in charge of the bigger picture set up their institutions to make sure that their vision was aligned with the realities of the different specific microcosms of the conflict, including both martial and political.

How to Align Decentralized Decision-Making with the Leadership’s Core Outcomes and Values

How did the British create a healthy, functioning relationship between commanders (upper management) and NCOs/junior officers (associates/mid-level management)? They found that lower level decision-makers could be allowed the freedom needed to exploit their specialized knowledge if upper management chose the right metrics to gauge whether these tactics were contributing to the overall strategic cause.

One of the specialists on my team is a local SEO specialist. The strategic vision is to use Google Maps and the local pack on Google to bring revenue-generating traffic to our clients’ websites. The truth is that the job is much more complicated than this, with different levels to it that necessarily abstract from the big picture.

A local SEO specialist needs to know things like whether average citation authority matters, whether bad citations can negatively impact local search traffic volume, how many reviews does a business need to be competitive, how we get a business more reviews, how important are local links versus relevant links versus other links, how we get more links, et cetera. There are dozens of moving parts to local SEO alone, enough that a specialist is needed to have specialist knowledge.

Even though the day-to-day concerns of a local SEO specialist are several degrees removed from the bottom line, I need that specialist knowledge to address that bottom line. But how do I know whether the local SEO specialist’s day-to-day decisions are working toward the bigger picture? By choosing the right metrics for the local SEO specialist to report to me on.

- Of those who saw the listing, what percentage clicked through to the website and/or asked for directions and/or engaged with the listing in some other way.

- Of those who clicked on the website, what percentage filled out a form or called the business?

Those two metrics can tell me a lot about whether the listings have traction and whether that traction is relevant to the goals of the business and our marketing.

And by using those metrics I can monitor the specialist’s performance without micromanaging a workload that that person understands much more than I do.

Bad metrics lead to bad outcomes. Suppose that my metric for the local SEO specialist is year-over-year data on local search traffic. That is, the metric is for him to show me whether traffic increased or decreased compared to the previous year. This metric tells me very little about the bottom line. Suppose the ranked for irrelevant terms that were easier to rank for but not the terms that bring people who want to buy the product. The metric might look really good, but it doesn’t necessarily correlate with what I really care about: is the business making more money because of our efforts?

Bad metrics lead to bad outcomes. During the Vietnam War, U.S. commanders cared about how many enemies had been taken out of action. U.S. soldiers found ways of inflating these numbers. The numbers looked great. Yet, by meeting the requirements of this metric the U.S. did not get closer to developing a doctrine that could provide victory in Vietnam because the metric did not correlate with the overall goal of providing a safe, stable environment for civilians to separate them from the insurgents.

A metric like the volume of road usage by civilians would better represent that overall goal and therefore would be a better metric to gauge the success of lower-level decision-makers (see David Kilcullen’s Counterinsurgency).

In a dental practice, one goal is to increase the effectiveness of the staff on the phone to bring in more revenue. The office hires an office manager to train the staff. How can the performance of the office manager be gauged? One metric is the close rate. This metric over time can show you whether the staff is getting more effective at closing business, and this metric correlates with revenue because the more deals that are being closed the more revenue you’re bringing in.

Metrics can become stale. For a long time, the Phillips Curve showed a positive relationship between the rate of inflation in an economy and the rate of employment. The Federal Reserve’s started to focus on employment as the metric to gauge the effectiveness of their policy. In the 1970s, this metric broke down. High inflation began to correlate with high unemployment.

Metrics can become stale. People figure out how to game them. If the goal is to increase the effectiveness of the staff on the phone and the metric is the close rate, that close rate can be manipulated. It might be easier to close a lower revenue patient than a higher revenue patient, and so your staff focuses on those leads to inflate the metric. This is inevitable and, rather than looking for a perfect metric, be dynamic and switch metrics if you start to see the relationship between lower-level decisions and upper-level vision break down.

What’s Your Experience?

How have you resolved issues stemming from the growing complexity of the business, the need for specialists, and the need to make sure specialists are meeting big picture outcomes? Is it different or the same as my, or rather Lt. Col. Nagl’s, approach?