Do you have a favorite genre of books?

What percentage of your reading does this genre make up?

If that percentage is very high, like above 50 percent, there are good reasons for branching out. Reading at all is great, and becoming rarer, so kudos, but if you want to take that next step and take your reading to another level, a multidisciplinary approach brings with it a lot of benefits that will help you become smarter, more well-rounded, and more creative.

As inspiration, I’m going to talk about 10 of my favorite books, hopefully motivating you to pick one or two of them up.

Before I do that, let’s talk about why multidisciplinary reading is such a good thing.

Why You Should Read A Lot and Widely

It’s About Fresh Perspectives

You’ll agree that ‘thinking out of the box’ is a good thing. What does ‘thinking out of the box’ really mean, anyway?

Someone who thinks differently, or approaches the problem from a different direction, is offering a fresh perspective that re-frames the issue. It’s about seeing the same thing a different way. This strength is not innate, it’s trainable and people who read widely have a big advantage because they are constantly exposing themselves to new ways of thinking.

It’s like when the light hits someone’s face from one angle, how you see that face — which characteristics stand out — can be dramatically different to how you’d have seen it had the light struck from a different direction. The shape of the nose or eyes may look different, or even the skin tone can change. You can only truly understand something if you’ve pointed the light on it from every angle.

Reading different perspectives is as important in an inter-disciplinary context as much as it is in an intra-disciplinary context. For example, as an economics student, I put a lot of emphasis on reading conflicting points of view. When people disagree with each other, they’re typically not just disagreeing, they’re talking over each other. In other words, they’re seeing different things, and that exploration of what other people are seeing that you aren’t is not only absolutely fascinating, it’s also highly educational.

Reading outside the discipline is equally as important when it comes to learning new perspectives. Let’s dig into that.

How to Abstract and Generalize

I’m a big fan of Friedrich Hayek. Not everything he wrote or said is right, but his approach to economics was incredibly unique and, in many ways, path-making. His influence on the profession is absolutely undeniable, at very least because of his paper, “The Use of Knowledge in Society.”

Basically, Hayek builds on previous arguments that explained how money prices help coordinate economic activity by tying it into the role of knowledge. For example, a fall in the supply of steel impacts how buyers use it because it becomes scarcer. The problem is that there’s a lot of steel producers and they all affect the supply of steel marginally; furthermore, there’s a lot of steel buyers. Word-of-mouth communication isn’t realistic. Money prices help capture this information and communicate it indirectly— an increase in the price of steel communicates that it’s becoming scarcer and influences its use.

Hayek had a specific advantage when it came to seeing this relationship between knowledge and prices. Before he was an economist, he was a theoretical psychologist and his work was partly focused on the connection between sensory experience, our nervous system, and our brains, and he came up with a theory on how this decentralized system communicates internally to give human beings the capacity to act.

By generalizing what he had learned in theoretical psychology and applying the abstract concept to economics, he was able to come up with a paper that has deeply influenced the world and the profession.

While I’m no Hayek, not even close, I do much of the same thing when I abstract and generalize lessons from books in one discipline and apply them to another. For example, when a book on Alexander the Great and the logistics of his army gives insight on what it takes to successfully run a business. Or when a book on counterinsurgency provides applicable lessons on coordinating a team in a necessarily decentralized organization.

By reading and practicing this art of generalizing and applying lessons, we get better at thinking outside of the box. In fact, much of the thinking has already been done, we just need to focus on the application.

Different Disciplines Have Merits of Their Own

Multidisciplinary thinking doesn’t stop at abstracting from one world view and applying it to yours. The best approaches are often multidisciplinary in a more explicit sense.

For example, you can’t separate marketing and behavioral psychology. Neither can you separate marketing from business. If you’re only reading marketing books, then you’re missing out on other subject matter that’s, ironically, needed to excel in the area you’re focusing all of your attention on.

Likewise, behavioral economics marries psychology and economics, because economics alone can’t explain why humans act the way they do. Traditional economics tells us humans are rational and seek to maximize the net benefits they receive from their actions and decisions. It’s an important baseline to have because it gives us a starting point, but it took the application of psychology to get a more complete picture of how humans actually act.

All the same, you can’t run a business without understanding how to build a relationship. And you can’t be the most effective manager you can be if you only understand the technical aspects of the job, but not the role that emotional intelligence plays.

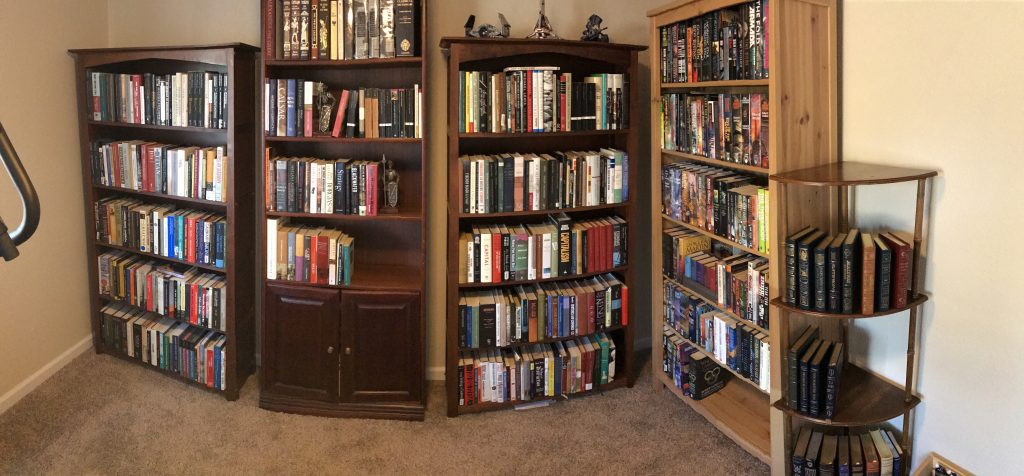

The Anti-Library

Nassim Taleb, a controversial statistician, likes to bring up the example of Umberto Eco, who owned an expansive private library of some 30,000 books. An individual can’t read 30,000 books, of course. Let’s say the average human lives until the age of 80. That’s 29,200 days in a lifetime. Even if you read a book a day, you wouldn’t reach 30,000.

So why own so many books?

Because those books are physical manifestations of our ignorance. And it’s the acknowledgment of our ignorance from which we get our intelligence, because only by knowing what we don’t know can we have the humility necessary to correct our biases.

Even if you don’t read them all, owning a large multidisciplinary collection of books already puts you on your way toward a multidisciplinary approach to your life, relationships, and work.

10 Books You Must Buy

Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search For Meaning

If we have our own why in life, we shall get along with almost any how.

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

Few people survived Auschwitz. Frankl lost his wife there, as well as his mother and brother. How did he survive?

Frankl approaches that question from an analytical point of view, which is incredible because he wrote much of this while experiencing the holocaust. In fact, in many ways, the research that went into Man’s Search for Meaning was the reason why he survived. The research gave him a reason to survive.

He finds that the difference between life and death often came down to having a reason to live. Those who died of disease or exhaustion had given up in the wider sense. And Frankl says that without judgment; after all, what experience could be more difficult than living through the Holocaust as a victim? But, it was those who had a why, a reason for existing, who were more likely to survive because they were more likely to fight for survival under undeniable hardship and tragedy.

This is an amazing book and if you were to buy only one from this list, please make it this one.

On Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence plays a central role in all of our human relationships, whether it’s at work, at home, or with friends. More than empathy, emotional intelligence is about using our empathy in a multidisciplinary way to produce better results.

For example, a good leader knows what she’s feeling and what others are feeling, but a good leader knows that sensitivity is not always the best way to respond to tense or emotional situations. Sometimes, responding with authority or toughness is the right approach.

People who are emotionally intelligent aren’t just empathetic. They’re also:

- Self-aware — they know their strengths and weaknesses, and are confident in this knowledge.

- Self-regulating — they can control their impulses.

- Motivated — they seek to achieve for their own sake.

- Socially skilled — they know the tools to build rapport and can apply these tools in the right contexts and situations.

On Emotional Intelligence is not just a quick read, it’s also highly insightful, showing how emotional intelligence affects the bottom line and teaching how to institutionalize it in your life. Furthermore, it discusses emotional intelligence in settings where it matters at the individual level and settings where it matters at the group level.

All managers should be made to read this book.

Adrian Goldsworthy, Caesar: Life of a Colossus

Julius Caesar is a controversial figure. He was a great leader, without a doubt. He accomplished magnificent things. Yet, he could also be brutal and, seen through a modern lens, a murderer.

Goldsworthy’s biography is, hands down, one of the best books I have ever read. Not only is Goldsworthy’s style lucid, and not only is the book interesting in its own right, but Caesar’s life imparts on us valuable lessons.

First, Caesar was very lucky at times. There were moments where he could have died before he eventually did (44 B.C.), including while on campaign in Gaul. How different would history have turned out? Very different, most likely.

Second, while acknowledging the role of fortune, Caesar also knew what he could control and in those areas he was uncompromising. During the late Roman Republic, a man who wanted to be #1 not just among his peers, but in history, had to meet strict requirements. For instance, the minimum age requirement to become consul (roughly equivalent to the U.S. presidency) was 40. To be elected as consul at the age of 41 would have been a failure to Caesar. So, he made sure he did what he had to so that he could become consul at 40.

Caesar’s story is highly inspirational because it motivates you to be more aggressive where you can make a change, because time is finite. It’s filled with plenty of experiences that seem specific to that age, which was a different age all considered, but which can be generalized and applied to our modern world.

Friedrich Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order

The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.

Part of me wants to recommend Hayek’s Law, Legislation, and Liberty instead, but it’s in Individualism and Economic Order where you can find “The Use of Knowledge in Society.”

You’ll also find “Economics and Knowledge,” “The Facts of the Social Sciences,” and a three-part series on the socialist calculation problem.

Whatever your beliefs, the breadth of the topics discussed exemplifies Hayek’s multidisciplinary approach to economics and illustrates how this approach makes fresh, unique perspectives possible. You may not walk away a Hayekian, and that’s okay, but you will definitely be impressed by the sheer scope of Hayek’s knowledge and his ability to apply it to different problems.

The volume is also a great introduction to Hayek. Although some of his ideas have not stood well against the test of time, others have and you may just find yourself branching out to his other works. He’s certainly a thinker whose ideas are worth internalizing.

John Nagl, Learning to Eat Soup With a Knife

I’ve more fully covered this book here, but it’s worth mentioning again.

Since the beginning of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, counterinsurgency has become an important area of study because, the fact is, most countries perform very poorly as counterinsurgents. In fact, Nagl seeks to extract lessons from the success of the British in Malaysia and compare it to American failures in Vietnam, offering insights on how to better combat and marginalize insurgencies.

If you’re not really interested in counterinsurgency and military history, Learning to Eat Soup With a Knife still has a lot to offer. The nature of counterinsurgency is that a counterinsurgent must operate through a decentralized system. The reason for thi is because insurgencies are not just about war, they’re also about politics and local relationships. This gives small units on the ground a central role in counterinsurgency, and if an army is not built to facilitate communication and flexibility between small units and higher level officers, the system will fail.

There are broad parallels with business, especially businesses whose teams operate in a knowledge economy. That is, when each member of your team has highly specialized knowledge that a manager won’t have, and doesn’t want to have (because a manager has to focus on the bigger picture), the system needs a method of communication and flexible, multi-level decision-making.

By drawing abstract lessons from Nagl’s book, we can apply them to our teams and learn from the experience of others rather than have to learn it the hard way.

James Buchanan, The Calculus of Consent

Nobel-winning economist James Buchanan has become a somewhat controversial figure as of late because of his views on the privatization of education and how these views interacted with what was the center of domestic politics at the time, the de-segregation of schools.

I don’t want to comment on that, but neither should it dissuade you from appreciating Buchanan’s intellectual contributions. You don’t need to like him to read and learn from his works. After all, John Keynes — the single most influential economist in history — was an antisemite. But, like economist Chris Dillow writes, “[H]is view of Jews is irrelevant in assessing the relevance of Keynesian economics today; we should avoid the “poisoning the well“ fallacy.”

The Calculus of Consent is personally one of my favorite books. It’s, to be certain, not light or easy reading. It can get very technical. In its totality, it’s an attempt to model constitutional democracy, or the institutions of a republic, using economic tools. It poses the fundamental problem of wanting to include as many people within the decision-making process as possible (democracy) and dealing with the reality that the more people you include, the more difficult it is to reach a decision that makes everyone happy.

Buchanan suggests that’s the role of the constitution, which sets the rules of decision-making. If we’re aware that we can’t satisfy everyone, we can develop a constitution as a society that at least agrees to a fair set of rules. If the decision-making process follows these rules, then the decision is legitimate. He also shows, for example, how a bicameral legislature, with the right rules, can achieve greater democratic inclusivity than a unicameral legislature. He also discusses how pressure groups (special interests) impact the decision-making process and how we can develop rules to control this, the role of logrolling (vote trading), and under what conditions which voting rules are best.

The book is, at its roots, a multi-disciplinary endeavor. It’s not necessarily all correct. Nothing written by a fallible human being is entirely correct. Nevertheless, this book is a great resource for those who, aside from being interested in the subject, want to learn:

- How to structure your thinking by modeling.

- How to produce valuable, unique insight by mixing tools, techniques, and understandings from different subject matters.

- How to build an overall rule structure that can bring fairness to the internal processes of your company.

John Rawls, A Theory of Justice

Rawls is possibly the most important moral and political philosopher of the late 20th century. It’s safe to say that A Theory of Justice has influenced almost everyone practicing in the field, and it serves as a foundation for most modern liberal moral theories. Mind you, that’s liberal as in pluralist, not liberal in the same sense that the word gets thrown around in contemporary political discourse.

I read A Theory of Justice almost as a matter of luck. It was required for a week-long graduate seminar taught by political philosopher Jeffrey Friedman and it completely changed my beliefs in the role of government and redistribution.

Like The Calculus of Consent, this book is not easy reading and there’s a lot to it, more than I could possibly hope to cover in a few short paragraphs. Furthermore, Rawls would go on to reconsider and expand on different elements.

It’s in A Theory of Justice where Rawls develops his idea of the original position. Imagine that you, along with everyone else, get pulled out of this world and stripped of all of your titles, all of your wealth, everything that makes you who you are. You’re told that when you return, you have no idea who you’ll be or what position you’ll hold. You could return as CEO of a Fortune 500 company, or you could very well come back as a fast food worker. Not knowing what station you’ll hold in life, what’s the minimum standard of living you’re able to survive at?

Whatever your answer is, that’s the minimum standard that should be applied to everyone.

It’s a powerful thought experiment that sets the tone for his work and gives motivation to discover the principles that ought to inform redistribution and government aid to different groups within our society.

I mention John Rawls on this list because it had such an impact on my way of thinking. I’ve always been conservative-leaning and it was this book that jarred my beliefs so much that I had to change them. What could be a more powerful compliment to a book than this one?

Cixin Liu, The Three Body Problem

Originally written in Chinese, The Three-Body Problem is a very smart science fiction book. The premise revolves around an alien race that invents a game that seeks the brightest minds to solve a long-standing problem. You see, this alien planet has two suns and the orbits are irregular, causing the planet to be periodically scorched and forcing that alien civilization to rebuild time-and-time again.

There’s, of course, a twist toward the end that I’d rather not reveal. On its own, it’s a spectacular read. In fact, the whole trilogy is fantastic.

Apart from a great story, Cixin Liu also brings to the table something that most science fiction readers have never experienced: Chinese literature. It’s written in a very different style, built on different cultural beliefs and assumption, and even serves a historical window into post-revolutionary China.

One of the greatest challenges to empathy is being able to understand cultures and ideas alien to our own. If we can’t identify, it’s more difficult to empathize. This comes down to perspective. If we’re not accustomed to certain perspectives, it’s hard for us to accept them as legitimate. Thus, what I appreciate about The Three-Body Problem is how Cixin Liu is able to package a fresh and invigorating perspective into a page-turner novel.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

Be tolerant with others and strict with yourself.

I finally read Meditations on the recommendation of one of my team members, and I wish I would have earlier.

Marcus Aurelius was Roman emperor during the late 2nd century C.E., and he was the last of what are termed the “five good emperors.” If you remember, he was the emperor at the beginning of Gladiator (the movie with Russell Crowe).

Meditations is a collection of notes and reflections, many of them having to do with ego, humility, and how to use hardships to motivate. They read almost like affirmations; personal reminders to himself on how to be a better, happier person. For example:

Very little is needed to make a happy life; it is all within yourself, in your way of thinking.

What brought Marcus Aurelius to write down his personal reflections on life, we don’t know. John Tzetzes, who lived in the 12th century, claimed that Meditations was written for Aurelius’ son, Commodus (the really bad emperor in Gladiator). They weren’t meant to be published, but who could resist the temptation of making his reflections available to a wider audience?

Marcus Aurelius’ writings are among the most popular guides on stoicism. Like with everything, read it with a critical mind. But definitely read it. When’s the last time you could claim you’ve read something written by a Roman emperor?

Simon Sinek, Start With Why

Why do people buy from Apple? Or Zappos? Or from you?

As Simon Sinek says, “People don’t buy what you sell, they buy why you sell it.”

That’s the question that Sinek motivates you to answer through this book. The reason why the question, and the answer, is so important is because, whether you recognize it or not, your ‘why’ dictates your ‘how’ and your ‘what.’

Take, for instance, Zappos. They are known for an incredible customer service. That level of service is a product of their overall philosophy, which seeks to “wow” the buyer by making the shoe shopping experience as streamlined and easy as possible. Every aspect of their company takes shape from these core motivations, from the core values that inform the decisions they take.

Without clarity of our core values, we can’t have clarity in our processes, policies, and actions. We can’t have clarity in how we communicate the why if we don’t know what it is. Finally, you don’t have clarity in the internal standards you hold these elements to. The experience you provide to your customers suffers as a result.

Start With Why is a very quick and easy read, and it’s for everyone, especially business owners and leaders.